Nature Conservation 2025 — 31. 7. 2025 — International Nature Conservation — Print article in pdf

Nairobi National Park – Nature versus Transport Infrastructure

Canberra, Seoul, Saint Louis, Chicago, Warsaw or Nairobi. What do these famous cities have in common? Unlikely as it may seem, national parks have been declared in their immediate vicinity or even within them. Yet only one of them can boast the unofficial title of the World’s only Wildlife Capital. Kenya’s capital city is the holder of this title, thanks to the national park of the same name.

I think having land and not ruining it is the most beautiful art that anybody could ever want.

Andy Warhol: The Philosophy of Andy Warhol (From A to B and Back Again) (1975)

How it all started

And indeed. For many visitors to sub-Saharan Africa, Nairobi National Park provides the first ever encounter with the still breathtaking nature there. And it has been doing so for 84 years.

British colonists arrived in the area where the national park is, at that time inhabited by nomadic Maasai and settled Kikuyu, in the late 19th century. But the real turning point came in 1895, when Britain’s Queen Victoria fought an imaginary duel with her grandson, Kaiser Wilhelm II of Germany, over who would be the first to reach the largest lake on the African continent, which had borne her name for almost four decades, by rail. Kenya was then part of British East Africa, while neighbouring Tanzania was called German East Africa. Incidentally, evil tongues claim that it was because of the German and Russian rulers of her kinship that the woman over whose realm the sun did not really set had herself named Empress of India, so as not to remain “merely” queen.

Nairobi National Park is located just seven kilometres from Kenyan capital city’s centre with a typical skyline. © František Pelc

Her Majesty’s subjects secured Albion’s victory by bringing from British India some 36,000 coolies and artisans, drawn mainly from the poor villages in the Punjab in then British India. Each coolie signed a contract for three years, which were by no means a relaxing holiday. The reason for the railway’s construction was clear: steam locomotives were able to transport not only goods, especially ivory, but also soldiers quickly and in large numbers on the Mombasa-Lake Victoria line: they thus helped to ensure dominance of the entire strategic region of the African Great Lakes. The cost of building the line eventually amounted to almost 5% of the then astronomical annual budget of the United Kingdom. Therefore, the sarcastic politician Henry Labiouchere nicknamed it the Lunatic Line.

In 1899, a large working army arrived with sleepers and rails to the area which the Maasai, who were no match for the warrior Indians of the Great Plains, called Enkare Nairobi, the Place of Cool Waters, referring to the cold stream which flowed through the area. Thus, the builders found an ideal location to establish an important rail depot there: it was at an elevation of almost 1,700 m above sea level, so there was no risk of malaria, it had a mild temperate climate and, last but not least, it offered abundant water resources as a permanent supply.

The railway running through Nairobi National Park was built by a Chinese company with money granted as a loan from a Chinese bank. © František Pelc

With the rapid expansion of the city into the surrounding countryside and the development of agriculture, the abundance of not only the iconic fauna species in its surroundings had rapidly decreased. Although part of the area was included into the Southern Game Reserve, where hunting, a traditional pastime of British men, was banned, the restrictions did not apply to other activities. Therefore, hunting was not permitted in the reserve, but nearly every other activity, including cattle grazing, dumping, and even bombing by the Royal Air Force (RAF) during pilot’s training was allowed there. As in so many other cases, it was one man’s stubbornness that finally decided everything.

The Southern white rhino (Ceratotherium s. simum) was introduced into Nairobi National Park.

© Jan Plesník

Common ostrich (Struthio camelus) prefers open land including East African savanna. © Jan Plesník

Mervyn Cowie had already been born in Nairobi and when he returned to Kenya in 1932 after nine years of studies in the United Kingdom, where he graduated from the prestigious Oxford University, he was literally horrified recognizing how the number of the large mammals had depleted around his birthplace during his nine-year absence. But the local British colonial authorities opposed the establishment of a national parks right next to Nairobi. The tenacious Scotsman therefore decided to use a trick that today we would call at best fake news, at worst pure disinformation. Playing devil’s advocate to push public opinion against hunting, he wrote a letter to a much-read local newspaper signed „Old Settler“ and proposing the slaughter of all of Kenya’s wild animals. There was public outcry against this suggestion, and the government was forced to act, and formed a committee to examine the matter. This was indeed the first in Kenya to be proclaimed on 16 December 1946, and Cowie became its first executive director. In it he introduced a model, still widely applied, whereby the bulk of the funding for the protected area management came from tourism: moreover, following the American national park model, Maasai pastoralists were removed from their landst.

|

Noah’s Ark for rhinos Nairobi National Park is one of a limited number of places offering safari participants the opportunity to see both species of African rhino in the wild. |

|

As recently as the early 19th century, more than one million black rhinos (Diceros bicornis) roamed the African savannah. Its population reached an imaginary bottom in 1993 as a result of massive hunting: no more than 2,300 specimens left across a huge area of its original distribution range. Today, this remarkable odd-toed ungulate species numbers 6,500 individuals: however, the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) continues to classify it as Critically Endangered worldwide at a global level. Nairobi National Park harboured 101 of these animals in May 2024: the population reach the highest density in Kenya there. At the beginning of 2024, 21 black rhinos were transferred from the park to the private Loisaba Reserve in the north of the country. As black rhinos are browsers, eating high-growing vegetation out of trees and shrubs, they tend to seek habitats with shrub or tree cover. Therefore, visitors to Nairobi National Park are more likely to see southern white rhinos (Ceratotherium s. simum) seeking open spaces where they graze peacefully on grass in small family groups. But these animals are not autochthonous there: they are native to South Africa and 11 animals released into Nairobi National Park have founded a population of 31 individuals today. In 1895, there were only a few dozen white rhinos left in the world, concentrated at a single site in South Africa. A careful search of the archives has confirmed that there are, after all, a few more rhinos left than previously thought. The efforts of the South African State Nature Conservancy and, in particular, of local farmers who have begun to keep rhinos on their fenced properties have resulted in a gradual increase in their number. Currently, 16,800 specimens live in the wild and in semi-preserves on the black continent, despite a recent huge wave of poaching. |

What Nairobi National Park has to offer today

The development of Kenya’s capital, one of the fastest growing cities in the world and currently home to 4.4 million people, has led to Nairobi National Park confirming its reputation as a protected area literally on its doorstep: it is just seven kilometres from the city’s centre. It covers 117 km2, only slightly smaller than the Český kras/Bohemian Karst Protected Landscape Area (Central Bohemia), and is mostly covered by typical East African savannah, i.e. open wide grassland plains with scattered Acacia spp. bushes. The uplands in the western part of the park are covered by dry forest, while in the south, along the permanent watercourse, the Mbagathi River, a floodplain forest growth has developed. Apart from the occasional deep rocky valleys and gorges, visitors to the park cannot fail to notice the rocky slopes hosting several notable species of vascular plants such as the monocotyledonous Murdannia clarkeana.

The proximity to the highly populated capital city has forced the fencing of the national park: electric fencing lines its northern, eastern and western boundaries. In contrast, the southern boundary, formed by the Mbagathi River, connects to the open landscape of Athi - Kapito, where large ungulates migrate in and out of the park. While the regular movement between the Serengeti in Tanzania and Kenya’s Masai Mara, aptly referred to as the Great Trek, is well known to nature lovers, it is less well known that more than a million of these mammals used to make the journey between Kilimanjaro and Mount Kenya. The founding of Nairobi has interrupted that migration: rather, the northernmost point of the now much smaller migration is the national park itself.

Despite its small size by African standards, Nairobi National Park hosts more than 100 mammal species, at least 60 amphibian and reptile species, 516 bird species and half a thousand vascular plant species. However, it is the charismatic larger mammals that attract tourists to the national park the most. They can observe, inter alia, lions (Panthera leo), leopards (P. pardus), Cape buffalo (Syncerus c. caffer), cheetahs (Acinonyx jubatus), spotted hyenas (Crocuta crocuta), African buffaloes (Syncerus caffer), Masai giraffes (Giraffa tippelskirchi) and hippos (Hippopotamus amphibius). Of the famous Big Five, only African bush elephants (Loxodonta africana) are missing from the park. Fearing continued conflicts with humans, the local elephants have been moved to the Masai Mara National Reserve. On the other hand, Nairobi National Park is one of the most important sanctuaries protecting both Africa rhino species (see box on previous page).

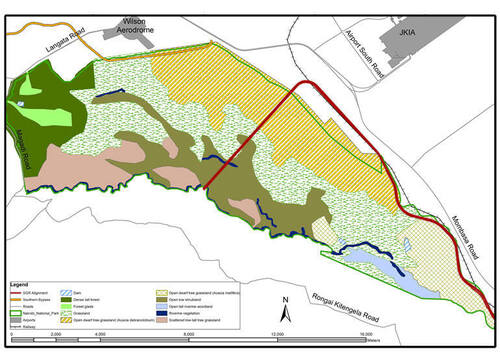

The Standard-Gauge Railway passes through the core of Nairobi National Park (red line). © Jan Vrba

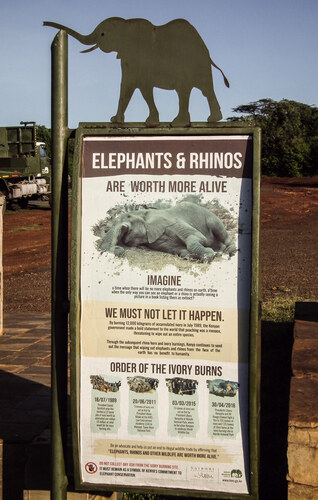

Close to the Nairobi National Park Main Gate there is a site where seized ivory or rhino horns have been several times publicly burnt. © Jan Plesník

Chinese capital was supposed to solve the problems with the Lunatic Line

The ravages of time have also taken their toll on the Mombasa-Lake Victoria railway line. Due to poor maintenance of the rails and trains, the journey from Nairobi to Mombasa took 24 hours at the beginning of the millennium, twice as long as in the previous decade. At that time, only half of all lines in the country were operational. But in 2011, the Kenyan government decided not to upgrade the Lunatic Line but to build an entirely new line from Mombasa to Uganda’s capital Kampala. This is the largest and most expensive infrastructure project since Kenya’s independence in December 1963: it will cost the state at least USD 3.6 billion (CZK 81.5 billion).

The financing of the costly construction was by a loan from the solved Export–Import Bank of the Republic of China (Chexim) covering 90% of the cost, while the Kenyan cabinet will pay a tenth. The line will not be electrified, with diesel locomotives running at an average speed of 120 km/h, reducing the journey from Mombasa to Nairobi to four hours. Companies from what was until recently the world’s most populous country have pledged to employ up to 30,000 Kenyans in the construction.

In December 2015, disturbing news leaked that the new line would run right through the heart of Nairobi National Park. The Ministry of Transport there subsequently commissioned an Environmental and Social Impact Assessment (ESIA) in accordance with the domestic law. Its results were described by experts as dubious and manipulated, as they visibly favoured the government’s preferred route. Moreover, of the seven options considered, five passed through the national park and the remaining two also encroached on it, although within its boundaries. Any options that bypassed the park completely were not considered at all: - the government would have had to buy up private land.

And the result? Since 2019, the landscape scenery/character in the legendary national park has been disturbed by a six-kilometre single bridge built on columns 18 metres above the ground. To limit vibrations, the 4 x 4 m columns had to be buried deep into the ground. It has been well known that the environmental impacts of linear structures extend far beyond them. Not only noise, but also pollutants from the construction, operation and maintenance of the the Standard Gauge Railway connecting Mombasa and Kampala affect the wider environment, despite the installation of numerous noise barriers. Experience shows that railways or roads through previously little affected protected areas encourage the introduction of invasive alien species, increase poaching and lead to changes in wild animal behaviour. Meanwhile, a tunnel has been built under the A2 motorway near Mount Kenya, which is also used by elephants.

To be objective, not all environmentalists criticize the construction of the bridge. Some point out that running the line on the ground would fragment the national park’s landscape much more, and the rails would be a difficult barrier for many animals to overcome. According to the late Kenyan scientist and conservationist Richard Leakey, it is most important that Nairobi National Park is not diminished.

According to the local press, the original plan was to repair only the damaged parts of the over 100-year-old railway in the existing corridor, which the World Bank was prepared to support. In the end, the chosen solution brought an entirely new construction there, including the above cutting through the national park. During the implementation, the investment increased considerably compared to the plan, which was criticised by some opposition political bodies. It is an open secret that the construction was also linked to corruption. Eighteen actors were eventually convicted. The beginnings were also difficult for the actual operation. Due to the lack of modern locomotives, coaches and carriages as well as the charges for using the new railway, much of the goods, including mined minerals, have been are transported by heavy trucks from the coastal areas to Nairobi and the surrounding areas. The state of the road between Mombasa and Nairobi is consistent with this.

Most of Nairobi National Park is covered by East African savannah. © Jan Plesník

The best time to watch Grant’s zebras (Equus quagga boehmi) is the dry season, when they concentrate close to water sources in the national park. © Jan Plesník

It’s not just about the actual construction

Kenya is often considered a model country on the black continent when it comes to nature conservation and landscape protection. The country has introduced some surprisingly strict measures: e.g. it is forbidden to own ivory, use plastic bags or hunt wild animals for trophies. In the opinion of numerous scientists and professional or voluntary conservationists, its long-established reputation has suffered considerable damage with the construction of a busy railway in the core of the national park. The project sets a bad precedent that will not affect only all of Kenya’s protected areas but also other African countries who look up to Kenya as a positive role model for wildlife preservation and environmental protection. Thus, there are legitimate concerns that other sub-Saharan countries will simply say: If Kenya can do it, why can’t we.

Kenya, like many other African states, is in debt to rich China, and is currently the fourth most indebted African country, which may bring many socio-economic and political problems in the future. However, among all the question marks and reservations, the routing across the area of a small national park on the outskirts of a large city stands out. We are convinced that a more economical solution could have been found, at least at the park’s boundaries. The length of the drive would have been increased by fifteen minutes, but the integrity of the park would have been better preserved there. Regrettable. ■

- - - -

Cover photo: The Newly built railway significantly disturbed landscape scenery/character in Nairobi National Park. © Jan Plesník

- - - -

The list of references is attached to the online version of the article at www.casopis.ochranaprirody cz.