Nature Conservation 2021 — 10. 6. 2021 — Research, Surveys and Data Management — Print article in pdf

How We Do (not) Implement the Water Framework Directive in Improving the Morphological Status of Wat

Data show that, in the 1990s, 28.4% of the total length of the Czech Republic’s watercourses were unfavourably modified, which is tens of thousands of kilometres of the river network. According to the current National Biodiversity Strategy of the Czech Republic, the country’s current optimistic targets are at least 300 km of restored watercourses for the 2016–2025 period. The status of watercourses and related floodplains has therefore not seen any significant improvement since the 1990s. Compared with biological and physical/chemical quality elements, monitoring and enhancement of the morphological status of the country’s watercourses has enjoyed a less significant position in the long term. However, apart from the “aesthetical” point of view, its improvement is also of unquestionable importance in terms of water retention in the landscape, flood protection, and drought management. It is therefore a topical issue in society.

Water Framework Directive requirements

In joining the European Union (EU), the Czech Republic (CR) committed itself to transpose the Water Framework Directive (WFD, European Commission, 2000) into its legislation and to consequently implement it. The WFD´s main aim is to avoid further deterioration of water ecosystems, to protect and conserve them and to enhance their status by appropriate measures (Fig 1). Pursuant to the WFD, the status of surface waters is determined by ecological or chemical status, depending on which is worse. The essence of the approach is to determine the current status of watercourses and, if good status has not been achieved, to design and implement measures that will achieve the good status. Simultaneously, active factors are set in each water body and related to the assessment of that body’s status. Ecological status is determined on the basis of the status of biological, hydromorphological, chemical, and physical/chemical quality elements. The purpose of evaluating the status of hydromorphological quality elements is (as is the case with chemical and physical/chemical quality elements) to obtain information on whether hydromorphological conditions enable achievement of the required quality of the biological quality elements and the required ecological status (e.g. potential) of the watercourse.

Figure 1: WFD objectives: To prevent further deterioration and protect and

enhance the status of aquatic ecosystems through specific measures (source:

Peter Pollard, the responsible author of the European Union Water

Framework Directive)

Hydromorphology – where did it come from?

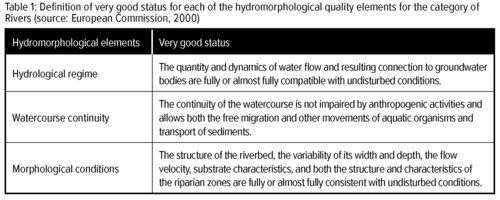

The WFD requirement for the quality of hydromorphological elements (see Tab. 1) was far from being the first-ever impulse in monitoring the hydromorphological status of watercourses.

In both Western Europe and North America, where fluvial morphology research had had a long tradition, methods for assessing the hydromorphological quality of rivers had been developed, along with studies defining the target status of restoration measures, for several decades by the time the WFD was adopted. It was therefore very important and necessary to anchor the trend in the EU legislation.

Subsequently, efforts to develop evaluation methods as well as design and implement restoration measures have increased in the EU Member States since the time the WFD entered into force. Many methodological approaches have already been developed, as mentioned by Belletti et al., (2015). Methods have been elab-

orated for the specific contions in the Czech Republic, whether based on field surveys (e.g. Matoušková, 2003, 2008; Langhammer, 2007, 2008, 2014; Langhammer & Hartvich, 2014) or evaluation using available input data (Králová, 2013; Kožený et al., 2019).

When evaluating biological elements, hydromorphology is only auxiliary, so do we need it at all?

The role of hydromorphological elements as a part of the ecological status is, pursuant to the WFD, “only” in establishing conditions for biota; however, this is the very point that seems to be a problematic issue since the relationship between biological elements and hydromorphological conditions of watercourses (i.e. the response of the biota to hydromorphological conditions and changes) has still not been described to a sufficient extent.

In addition, there is a relatively large degree of variability in physical and geographical conditions in the Czech Republic, which also applies to the types of watercourses (Fig. 2 & 3). Consequently, to evaluate hydromorphological conditions, it is essential to establish baseline conditions for each type of watercourse (i.e., find sites or establish conditions of river systems with minimal anthropogenic influence) that serve as a benchmark in the assessment and represent the target status of the measure.

Figure 2: Naturally straight channel of the upstream stretch of the Jizera River

with a considerable gradient. © Kateřina Kujanová

As a starting point for the draft measure, it is necessary to assess which effects are of such importance that they cause changes in hydromorphological conditions, thereby preventing the achievement of good status in biological elements. According to the data model (Vyskoč et al., 2019) based on the EU indicative document for the reporting river basin management plans, the types of effects on the hydrological regime and morphology are divided into four areas: water abstraction/transfer; modifications along a watercourse; dams, obstacles/barriers and locks; and hydrological changes. There is also a need to specify the reason why these changes were made (agriculture, hydro power, fish farming, flood protection, water transport, etc.).

Figure 3: A meandering channel of the Rokytná River before its confluence

with the Jihlava River. © Kateřina Kujanová

Opponents of EU requirements would certainly argue how complicated the process is. However, it should be noted that, even without any EU framework, measures such as the revitalization and restoration of watercourses and floodplains must be designed and implemented systematically, that is to say, on the basis of monitoring, through the stewardship and management of watercourses, and within a much larger number of watercourses. At the same time, the implementation of measures should be supported by a change in legislation. Removing unnecessary engineering (in particular the longitudinal technical regulation of channels, as well as treatment of weirs) is crucial in promoting restoration at a higher scale. Furthermore, it is very important that the disappearance of property linked to such engineering works is not perceived as negative, as it has been so far.

What data do we actually have?

We have long been monitoring physical/chemical parameters in watercourses in the Czech Republic and we have set up monitoring of biological elements. In both cases, this is a monitoring process underway in one established profile, representing the whole water body.

Hydromorphological elements were not systematically monitored in the Czech Republic in the first and the second cycle of planning. For the third river basin management plans, state-controlled river basin management authorities applied a procedure to determine major effects on morphology and the hydrological regime (Kožený et al., 2019). This was a procedure to assess the backbone watercourses (water bodies), rather than looking for impacts in the water body catchment area. Morphology, including watercourse continuity, was assessed through the available data for straightening (historical maps), provision of capacity (floodplain areas of flood frequencies for return intervals of 5 years Q5), vegetation and construction development (ZABAGED –Fundamental Base of Geographic Data of the Czech Republic), agricultural drainage (Agricultural Water Management Authority of the Czech Republic/AWMA data, 2010), migration/movement barriers and storage levels (Nature Conservation Agency of the Czech Republic´s data from the project “Developing a Strategy to Reduce the Impact of Fragmentation of the Czech Republic’s River Network”; here it should be noted that the data from this project do not cover the total length of the country’s water bodies). The influence on the hydrological regime was developed with a view to regulating the flow rates of water reservoirs, the abstraction of surface water and groundwater, and the re-discharge into surface water.

Thus, hydromorphological effects were identified to some extent, but the actual monitoring of hydromorphological parameters was not performed to a sufficient extent even for evaluation for the third river basin management plans. This is mainly due to the long time required for field mapping according to the officially approved hydro-ecological monitoring (HEM) methodology (Langhammer, 2014), as well as the generally underestimated significance of knowledge of the status in hydromorphological parameters. Since the Czech Republic has already been criticised by the European Commission (EC) for the absence of the status of hydromorphological elements, the above assessment of the significance of the effects was converted into a scale of evaluation of the status of hydromorphological elements. However, such an assessment of the hydromorphological status may not always be appropriate to the real situation, which may cause problems for the country in the future, e.g. in assessing the situation in future planning periods or in terms of the need for implementing and financing measures.

In the field or in the office?

An eternal discussion around hydromorphology is whether it is necessary to go into the field to collect new data or if evaluating the available remote data is enough. The truth lies, as usual, somewhere in the middle. An assessment should not be lacking input background data (e.g., historical route maps, facilities on watercourses, channel modification information). Some of the other indicators being assessed can indeed be established in the office by operation engineers of river basin management authorities or NCA CR water specialists; however, they do not know all the watercourses equally well in their territory. The field validation of certain parameters therefore only appears realistic if it were spread over the next few years, rather than weeks, and supported by a database application to process the information sourced. Another prerequisite is the rational range of parameters to be determined and the least degree of subjectivity in their determination as possible. This approach was successfully verified by the NCA CR in the monitoring of migratory/movement barriers implemented within over 11,000 km of watercourses (the previously mentioned project “Developing a Strategy to Reduce the Impact of Fragmentation of the Czech Republic’s River Network”, www.vodnitoky.ochranaprirody.cz).

Figure 4: Promoting the restoration of the Morava River near the town

of Štěpánov by the removal of historical bank fortification; new

elements to divide the channel morphologically and hydraulically were

produced from material from the dismantled fortification. © Jan Koutný

This supports the conclusion that we need a place to start from, and the sooner we start, the better. At the same time, it would be useful to take into account that many small watercourses are very similar to each other and that even a systematic approach can be based on “monitoring typical examples” and the similarity between these, which can be refined over time.

Current situation

In December 2018, the Czech Republic reported to the EC that almost 20% of the measures proposed in the second river basin management plans were focused on hydromorphological effects, that is, mainly on restoration projects. Of these, 7% have been completed and 41% are in progress. So everything seems to be fine, or at least on track. Although it has still not been possible to evaluate the change in morphological status due to the lack of data, when you go out and along watercourses across the cuntry, it is clear that the situation is not very optimistic…

Although the topic of improving the morphological status of watercourses has gradually become a common part of strategy papers and policies since the 1990s (including, obviously, the currently applicable second river basin management plans providing a number of measures to this end), many of the proposed measures remain just on paper. Despite available funds in the Operational Programme Environment funded from the EU budget and the landscape management schemes of the Ministry of the Environment of the Czech Republic, a maximum of twenty km of watercourses are revitalized annually across the Czech Republic. The reason usually mentioned for that fact is difficulty in preparation and consultation measures, particularly in terms of legal ownership. Although the improvement of the status of aquatic ecosystems and thus improvement of the morphological status of watercourses is the WFD´s primary objective and considerable efforts have been made in this regard, any improvement of the morphological status through restoration projects has been seen at the minimum percentage of poor-condition watercourses. There is much more improvement (in terms of extent) due to spontaneous restoration processes during succession in the ecosystems, meaning without human actions or perhaps despite such efforts.

While the implementation of watercourse restoration projects has been lagging behind, similarly complex flood-protection projects proposed by municipalities have been doing much better over the long term, while watercourse management authorities are often those that carry out such measures. The question therefore arises as to whether or not a similar “design and implement” model could be applied in the case of restoration or investment measures to promote restoration. However, this issue is strongly linked to the motivation for watercourse management authorities to implement such measures.

Promotion of restoration projects

Revitalization of regulated watercourse channels and measures to promote restoration processes (Fig. 4) are undoubtedly actions improving the morphological status of watercourses in line with WFD requirements. However, due to their complexity, revitalisation projects cannot “heal” any substantial portion of watercourses in the foreseeable future. As nature has been telling us for some time, a much simpler tool to improve the morphological status of a considerable length on watercourses is to encourage spontaneous restoration processes (natural processes gradually removing engineered watercourse channels), or to initiate such processes. Combined with ecologically-oriented management and maintenance of watercourse channels, the potential of such natural processes is considerable – restoration processes are underway gradually but constantly throughout the river network and are not subject to any administrative initiative. Therefore, identifying stretches of watercourses suitable for the restoration process should be a priority among the measures to improve the morphological status of watercourses for the third planning period.

Conclusion

Are we just trying to achieve the desired in the simplest way possible or have we really understood the meaning of the WFD and try to actually improve the status of watercourses through slow, gradual steps? Any systematic approach to identifying, in a consistent manner, significant effects across a water body’s catchment area and establishing the ecological status of the water body (including the relationship between biota and morphology) has still significantly been lagging behind. The same is true of proposing and, in particular, implementing measures in the event of a failure to achieve good status. We are at the end of the second planning period and it is clear that the morphological status of watercourses has not improved significantly in the Czech Republic. We could say that “perhaps in the next planning period we will do it”, but I would rather call on all the stakeholders (whether biologists, water engineers, planners, science, research and innovation foundations, watercourse managers, staff of the relevant authorities or the general public, who are not indifferent to the status of watercourses) to help include the hydromorphological aspect in putting the idea of systematic stewardship and improvement of watercourses into real life.