Nature Conservation 2020 — 25. 3. 2020 — International Nature Conservation — Print article in pdf

Kaziranga National Park – a Little Miracle in Overcrowded India

As students, we read Zdeněk Veselovský's book ‘Voices of the Jungle’ describing his stay in Kaziranga National Park. In addition to numerous interesting facts about wildlife bionomics, the reader will find a number of notes on nature conservation half a century ago. A very valuable article on the simplest problems of biodiversity management in this Assam park was published by Douglas Chadwick in National Geographic (2010). With some worries but also hopes, we visited this area in March 2019. However, the experience exceeded our expectations, despite many problems that persist in the national park. After all, over a hundred of the symbolic Indian rhinoceros (Rhinoceros unicornis) have been poached in Kaziranga in the last ten years, and the population around the park has grown by a third.

India under a magnifying glass

India, covering nearly 3.3 million km², is the 7th largest country in the world and, due to its geographical location, is sometimes referred to as the Indian subcontinent. Due to its huge area, a wide variety of environmental conditions can be found there, including tropical coasts and wetlands in the deltas of huge rivers, savannah, semi-deserts, tropical and subtropical dry, rain and monsoon forests, as well as the highest mountains in the world – the Himalayas. However, due to the long-term and extraordinarily high population (with nearly 1.4 billion inhabitants, it is a close second behind China); almost all natural communities have only been preserved in fragments. Indian population density reaches over 430 people per km², i.e. almost four times higher than in the Czech Republic. Although the annual population increase has fallen to 1% in recent years, it still means an annual population increase of 14 million people. Almost 60 cities have more than 1 million residents; the largest are the metropolises of Delhi and Mumbai, both of which have populations close to 20 million. Despite the undeniable economic development observed in recent years, India is still a poor country.

Kaziranga National Park: Location, Area, History

Kaziranga National Park (KNP) is located in the north-east of India, in the state of Assam, on the border between the tropics and subtropics. Thanks to the local monsoon climate, however, we can find truly tropical nature there. The rainfall is uneven, with most falling in June–September, and the total exceeding 2,200 mm per year. This geomorphologically rather monotonous landscape lies at 40–80 metres above sea level.

Wetlands and lakes make up about a tenth of Kaziranga National Park.

Photo František Pelc.

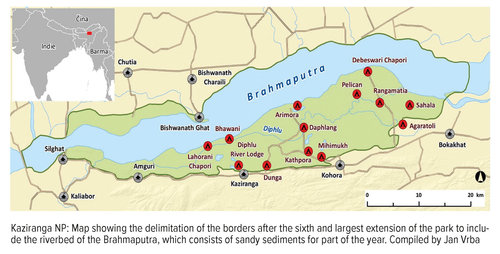

KNP has become a UNESCO World Heritage Site. The roots of its protection date back to 1904, when the enlightened Baroness Mary Curzon, after visiting and finding the territory almost devoid of animals due to mass poaching, urged her husband, working in the colonial administration, to enforce the protection of this magical corner of India. At that time the rhinos and other animals had been hunted almost to extinction. And she succeeded. Already in 1905, a reserve of 232 km² was designated here, which was gradually extended. However, the latest, sixth expansion of the park to include the riverbed and floodplain of the Brahmaputra was the largest: Thanks to the new 350 km², the total area of the national park has reached 860 km², which is above average in Indian terms.

Landscape and Biodiversity

KNP is part of the Indomalayan (Oriental) zoogeographical region and one of the hot spots of global biodiversity. This term refers to areas with high species richness, a high number of endemic species and a high degree of habitat damage by humans, mainly due to their large-scale disintegration and destruction. In order to be considered a “hot spot” of world terrestrial biodiversity, at least 1,500 vascular plant species (i.e. more than 0.5% of all known species) must grow there, and at least 70% of the original habitats had to have been lost.

The sandy-muddy floodbanks of varying magnitude and the riverbed

of the Brahmaputra, up to 10 kilometres wide, make up more than

a third of the area of the park. Photo František Pelc

The origin of the Himalayan hot spots is due to several causes. They are points of contact between the foot of the Himalayan ridge and the lowland on the floodplain of the Brahmaputra (translated as the Mother of Rivers), creating extremely varied environmental conditions. In the Tertiary period, the Indian plate crashed into the Eurasian mainland, creating the highest mountains on Earth along the line where the lithospheric plates clashed. A main reason contributing to the high productivity of the local ecosystem is the massive flooding as the Brahmaputra overflows onto its floodplain every year during the rainy season, covering two-thirds of the park, and making the whole park inaccessible to the public, but also bringing a huge amount of nutrients with it. Thanks to this source, we can also find population densities of various wild animals, apparently deviating from ecological assumptions. Last, but not least, long-term protection of the local environment also contributes to the preservation of high biodiversity. In terms of diversity and abundance of fauna, KNP can boldly compete with Africa’s most attractive parks on the savannah.

Red jungle-fowl (Gallus gallus), the ancestor

of the domestic fowl, is a rather slender and

shy bird. Photo František Pelc

There are six basic landscapes – vegetation formations – in the park. The vast area of the Brahmaputra floodplain is largely covered by flooded grassland communities, including elephant grass growing up to 6 metres high, whereas flooded savannahs, enriched with non-contiguous shrub and tree vegetation, also appear in the adjacent areas. More than a third of the park area is formed by the riverbed of the giant river with massive alluvia, with only sparse vegetation. Tropical wet and semi-deciduous forests form an important part of the landscape. Finally, we must not forget the permanent wetlands with lakes and pools of different sizes attracting many migratory and nesting birds.

Monsoon and semi-deciduous forests can be found in about 15%

of Kaziranga National Park. Photo František Pelc

Thanks to the high diversity of habitats, KNP is also very rich in avifauna. A total of 500 nesting and migrating bird species have been recorded here. In addition to dozens of exotic taxa, for example hornbills, parrots, barbets and flocks of Indian geese (Anser indicus), we had the opportunity to observe ‘our’ overwintering Eurasian snipe (Gallinago gallinago). This is one of the reasons why the park is classified by BirdLife International as an important bird area (IBA). KNP also hosts 56 reptile species, including 17 turtle species and 25 snake species.

The red-breasted eagle (Spilornis cheela) is a common

representative of the Indian avifauna. Photo František Pelc

Despite other richly represented groups of animals, however, the extraordinary species diversity and abundance of mammals plays an important role. Monkeys are represented by four species, including the western hoolock gibbon (Hoolock hoolock), one of the most endangered primates of all. Four species of deer (sambar deer, barasingha, Indian hog deer and muntjac) are important for the functioning of local ecosystems, both as grazers of vegetation and as prey for predators. Similarly to Africa, India also refers to the ‘Big Five’, but with a slightly different composition. Its representatives include the wild water buffalo (Bubalus arnee), sloth bear (Melursus ursinus), Indian elephant (Elephas maximus), Indian rhinoceros and the Bengal tiger (Panthera tigris tigris).

The Indian rhinoceros is out of immediate danger due to systematic protection

in Kaziranga NP, and unlike its African relatives, it loves to stay in the water.

Photo František Pelc

Wild water buffalo are threatened not only by habitat destruction and poaching, but also by hybridization with domestic buffalo. Nevertheless, the local buffalo population is thriving and already exceeds 1,800 individuals, representing about two-thirds of the global population. However, the hybridization has some limitations because it appears that while the male wild buffalo is able to mate with the domestic buffalo cow, female wild buffalo can only rarely mate with a male domestic buffalo, due to significantly different body parameters, so the introduction of domestic animal genes into the wild population may not be so dramatic.

The Indian water buffalo in Kaziranga NP forms one of the last strong populations

in the wild. Photo František Pelc

The vital population of Indian elephants in the park reaches about 1,300, and is a frequent cause of conflicts between wildlife and nearby farmers, whose labour-intensive agricultural crops can be significantly damaged by the elephants.

The Indian rhinoceros, along with the white rhinoceros (Ceratotherium simum), is one of the largest terrestrial mammals after the elephant and its weight normally exceeds 2 tonnes. KNP has a unique position in the protection of this archaic-looking species. After all, in the last census at Kaziranga, there were about 2,400 rhinos, or about 80% of the world population. We can say that observation of this species has been practically guaranteed for every ecotourist in recent years, which was not always the case.

The Indian hog deer is the most common deer in the park. It is a frequent prey

of the tigers. Photo František Pelc

The Bengal tiger is another treasure of Asian fauna. According to the latest official data, a total of 2,970 individuals are found in various scattered Indian protected areas, called ‘tiger reserve’. Nevertheless, the number of tigers in KNP has increased in recent decades, and now reaches around 100 individuals. Although it is one of the largest tiger population densities, not only in India, with each tiger occupying 8 km² of parkland, ordinary tourists rarely encounter a big cat.

Dangers from the Surroundings

The densely populated area around the National Park is covered by rice fields and tea plantations. Island-like remnants of declining forest formations only remain on the surrounding slopes. However, in times of flooding, when most of the park disappears underwater, they are a very important refuge allowing many animals to survive for several months. That is why the Assam government is trying to protect them more consistently from further destruction. Wildlife populations must migrate through populated and intensively cultivated areas, and the number of conflicts is increasing. On the road along the northern edge of the park, we saw dozens of signs confirming this fact and urging drivers to significantly reduce their speed to 20 km/h, which nobody adhered to while we were watching.

The development of ecotourism is key to a good level of nature protection.

Photo František Pelc

Overall Impressions

Kaziranga National Park is faced with many problems related to the surrounding dense population, intensive agriculture and poaching. Despite this, thanks to roughly 600 professional rangers, the park is managing to cope admirably. This is also due to the employment of a further 2,000–3,000 local people in ecotourism. Kaziranga NP is the destination of about 50,000 tourists annually, of which less than a tenth come from abroad, and many spend several days here. Rangers are armed and use an uncompromising approach against poachers.

What message can be found for nature and landscape protection in the Czech Republic? Although each comparison requires some simplification, following the way our hunters and farmers deal with the return of a few dozen wolves to our country, the wilderness coexistence model between Kaziranga NP and the neighborhood in densely populated and poor India can be of inspiration. The existence, care and development of the environment in Kaziranga NP are undoubtedly among the successes of not only Indian nature conservation; which is not such a common thing at present.