Nature Conservation 2020 — 25. 3. 2020 — Nature Conservation Legislation — Print article in pdf

Tree veteranisation, pollarding and girdling vs tree conservation

Selected issues of practical protected area management

We are currently observing changes in the landscape at an unprecedented rate. We do not have in mind here the often mentioned impacts of climate change, but particularly the consequences of changes in land use by man. A century ago, when a third of the inhabitants of the Czech Republic still made a living from agriculture and forestry and the average farm size did not even exceed 5 hectares (Kučera 1994), the landscape was in many ways exploited more intensively, but at the same time in a much more mosaic way. At present, only a tenth of them participate in land management, while industrialised farming takes place in large, consolidated areas and the management of economically marginal areas and traditional, more labour-intensive forms of farming have been abandoned.

The result is a progressing homogenisation of the landscape, changes in and loss of many habitats and communities, and an alarming overall decline in and extinction of many species. If we want to face this trend, nature conservation must make an effort to restore historical forms of management or their effects by realising appropriate compensatory measures. By default, efforts to restore grazing at suitable sites, mowing in a mosaic way (grassland cutting differentiated in time and space) attempting to compensate for the diversity that small-scale farming had naturally generated, etc. have already been included into ‘conservation management’. Also a wide range of other activities take place in the landscape, including many different forms of utilisation of trees and tree parts. Measures for the support of biodiversity must include the restoration of these historical management methods and compensatory procedures for the initiation and creation of habitats for species (particularly saproxylic insects) specifically bound to such habitats. In this contribution, we will have a look at special treatment of trees growing outside forests.

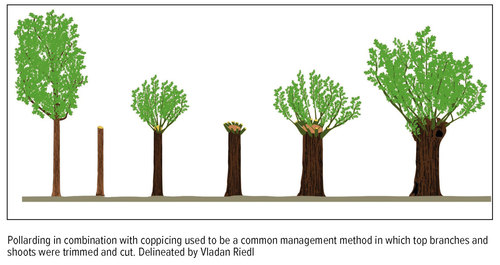

High stumps were often left in coppices, so coppicing mostly fluently passed

into pollarding. Restoration of a formerly trimmed oak. Photo Karel Kříž.

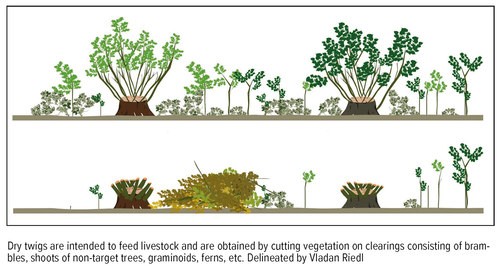

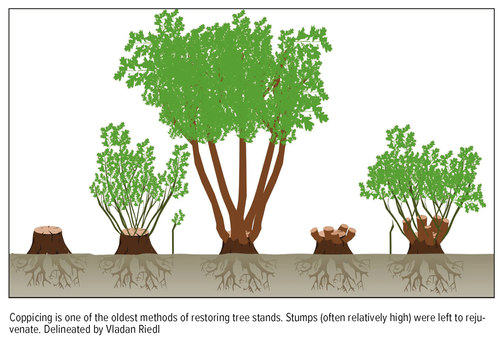

Before the advent of fossil fuels, wood was a much demanded energy source. It was even obtained at remote sites and hardly accessible places in the easiest possible way. At the same time, forests were exploited as a source of various materials, and all kinds of tree stands were used as a source of complementary biomass. Particularly municipal pastures, somewhere also mortuary lands and open-canopy forests, were used intensively for grazing. Commonly coppicing was practised here, branches were trimmed, etc. Also use was made of dry twigs and shoots and tree debris. In the case of trees growing along roads, in hedges and on land boundaries, pollarding was often practised. At the same time, trees were exposed to cattle activity and, last but not least, also to fire. These activities, together with more age- and species-differentiated forests and a higher percentage of old-age solitary trees (incl. old fruit trees) in the landscape, guaranteed permanent suitable conditions for the presence of saproxylic insects and other organisms bound to sunlit trunks, cavities, cracks and other microhabitats typical of senescent trees. Today, former municipal pastures, tall standard-tree orchards and coppices densely encroached with trees and shrubs, are often reclassified as woodland and managed as clearings, or are protected woodland left without deliberate felling. Pollarding and other ways of obtaining wood have been abandoned (Szabó 2010).

Trimming of pollard willows is best carried out in regular, roughly five-year

intervals in a way that the heads do not break apart under the weight of the branches.

Pictured: willows in Křivé jezero National Nature Reserve. Photo Vladan Riedl

Compensatory measures for habitat creation

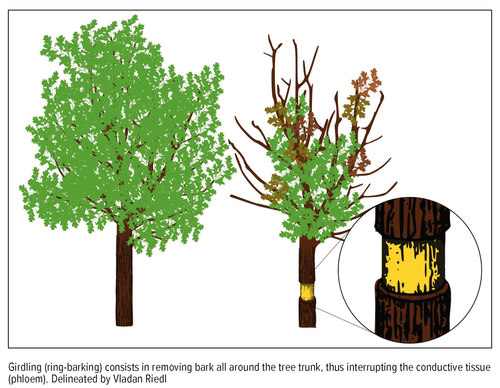

Many animal and plant species are existentially dependent on habitats through traditional management forms (Šebek et al. 2013). This is apparently related to the fact that at least some of these forms are similar to natural processes which used to have an impact on trees even without man. Tree trimming or pruning may be similar to the effects of large mammals, while girdling and coppicing create habitats similar to fire. All the more problematic is the fact that trees treated in this way gradually disappear from the landscape. Sites indispensable for the survival of many endangered organisms inevitably decline due to this (Čížek et al. 2016). Modern nature conservation is therefore searching for ways to compensate for traditional management forms with the aim of preserving conditions necessary for a favourable development of populations of various endangered species and communities. Such approaches include controlled veteranisation and other sorts of interventions on trees, which make it possible to accelerate the creation of habitats linked to more advanced tree development stages, i.e. aging and decay (for a detailed description of different methods, see Box). With regard to the degree of threat of different species bound to dying trees (or their parts – cavities), their usually slow development and low population dynamics (e.g. in the beetles Cerambyx cerdo, Osmoderma barnabita and Lucanus cervus, having a development cycle of several years) and also with regard to the uneven representation of trees of the appropriate age and condition, it is necessary to create habitat conditions with a relatively long-term perspective. This cannot be limited to just a preservation of the actual, often residual condition, which would also mean the loss of populations of species bound to it after death and decay of even well-maintained trees. Unfortunately, such a threatening scenario can be expected in many cases and will often be difficult to prevent (e.g. species associated with allees and similar groups of trees, some of which fall under the Natura 2000 network). The more important is the implementation of measures in areas which have a potential for maintaining particular species and their habitats in the long term. In many states of southern and western Europe, traditional management forms have partly been maintained to this day, while in other (e.g. northern) countries, restoration of these forms, initiated by nature conservation, has been practised for years (Alexander 2012, Cavalli, Mason 2003, Speight 1989, Read 1996, Unrau et al. 2018, Vignon, Orabi 2003).

A small-leaved lime tree can survive for centuries thanks to coppicing.

Its stump may reach a diameter of even 10 m and is a suitable habitat for

many species. The photo is from Děvín National Nature Reserve. Photo Vladan Riedl.

Creating habitats does not mean damaging trees

Legal limitations concerning the protection of non-forest greenery in the Czech Republic are based in the embellishment movement of the first half of the 20th century. It was a reaction to the then overexploited landscape (grazing, but also unregulated tree felling) aimed at maximum enforcement of tree preservation.

Current legislation (Act on Nature and Landscape Protection, since 1992) generally prohibits the ‘damaging and destroying’ of trees. At the same time, it empowers the Ministry of the Environment to define in an implementing legal regulation which interventions are or may be ‘damaging’ or ‘destroying’ and must thus be regarded as ‘illegal’. This empowerment makes it possible to define species or cases of such interventions also ‘negatively’, i.e. to determine in which cases an intervention may be legitimately considered permissible. The Ministry of the Environment has taken into account current expertise and conservation needs of endangered species and, in Act No. 189/2013, on the protection of trees and authorisation of tree felling, constitutes that “an intervention is permitted if it is performed with the aim of preserving or improving particular functions – for the treatment of a protected plant or animal species, as part of protected area management performed in accordance with the management plan or management principles, or as part of the management of a European Site of Community Importance (SCI) or Special Protection Area (SPA) performed in accordance with the set of conservation measures.“ Thus, whereas planning documentation, i.e. management plans or sets of conservation measures are the basis of the management of protected areas, SCIs and SPAs, the regulation on the ‘treatment of a protected plant or animal species’ is not bound to any other formal condition (not even that the protected species in question should occur at a site before an intervention).

In the case of protected animal or plant species, procedures must be based on expert documents, which may not only be rescue programmes or regional action plans, but also expert proposals as part of particular projects or measures (see below). Generally, in each individual case it must be assessed whether the legal principle of proportionality is maintained, i.e. whether an intervention is appropriate (if it can create the conditions necessary to enforce the populations of target species at a site), necessary (no alternative measures can achieve comparable objectives with regards to the treatment of a certain species at a site) and proportionate. The expert documents should thus provide information to answer these questions. It is, of course, also necessary to assess the needed measures with regard to the trees in question. In most cases, the benefit of saving a species will be considered greater than the damage caused to common tree species, but opposite situations may occur (extraordinarily robust trees, trees of high cultural value, etc.). If the measure is not initiated by a nature conservation authority, it is appropriate that the need and expertise of the proposal be approved by the relevant nature conservation authority, so that the initiator of the measure is certain that the interventions will not be evaluated as undesirable and disproportionate by supervisory bodies. It can therefore be recommended to pre-discuss a measure with the Czech Nature Conservation Agency, being the official nature conservation authority, and with the relevant regional authority responsible for species conservation outside protected landscape areas and national parks.

Do not underestimate project preparation

If a measure does not follow from nature conservation planning documentation (management plan, set of conservation measures, rescue programme), it is effective to make a project from which the objective of the measures, the necessity and the way effectiveness will be monitored are evident. It also needs to be assessed if a project requires other appraisals and permissions (e.g. exemptions in protected areas or because of the presence of a protected species) and whether the trees in question are not subject to heritage protection (e.g. in a castle park). As for tree protection, permission to perform particular inventions is not issued in accordance with Act No. 189/2013 (it is not felling). It is however advisable to inform the local municipality and also the wider public of the interventions in an appropriate way, in order to secure the necessary acceptance. In case a tree is located at the site of a protected monument, agreement must be reached with monument care authorities1.

A project may be based on existing professional methodologies, see e.g. ‘Conservation of saproxylic insects and measures for their protection’ (Krása 2015) issued by the Czech Nature Conservation Agency and ‘Methodology for the conservation of selected beetle species and their habitats’ (Konvička et al. 2017), and on methodologies for saproxylic beetle species important in the European context (Čížek et al. 2015), certified by the Ministry of the Environment. At present, a standard titled ‘Treatment of trees as a habitat of rare species’ (Pešout, Štěrba 2013) is being compiled. Also consultations with specialists are advisable because recommended approaches may have to be modified or specified according to the needs of a particular species.

Necessary change in approach

Just as land use by man changes, also the tools of contemporary nature and landscape conservation must develop. In this particular case it is obvious that the conservative conservation of trees outside forests and a range of woodland conservation instruments from the times of the Austro-Hungarian Empire have become outdated in many aspects. It is necessary to respond to the current state and utilisation of the landscape, the impacts of climate change, new challenges and current knowledge.

It is also clear that for reasons of capacity and economy, planned tree habitat treatments as indicated will always be realised to a very limited extent and especially in protected areas. However, protected areas will not save the existence of many animal species even with the best care. Traditional land use forms, which can be realised economically by farmers and foresters, need to be supported by adjusting subsidy instruments or also by legislation to be applied on a larger area. Further, environmental education can help improve the situation by informing the public on the need of leaving fractures and other tree damage not jeopardising its stability untreated.

A list of recommended literature is attached to the web version of the article at

www.casopis.ochranaprirody.cz

Note

1 Examples of areas where monument care and nature conservation interests are concentrated and where the methods of tree treatment had to be agreed on (incl. treating senescent trees, restoring tree stands, securing continuity of saproxylic insect habitats, etc.) are the horse-breeding farm at Kladruby nad Labem (Beneš et al. 2018) and the castle park in Vlašim (Hejda, Kříž, Pašek 2017).

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Lukáš Čížek (Institute of Entomology), David Číp (Czech Union for Nature Conservation), Eva Mazancová (Ministry of the Environment), Radek Hejda and Vladan Riedl (Nature Conservation Agency) for reading the text and comments on the article.