Nature Conservation 2024 — 30. 5. 2024 — On Nature in the Czech Republic — Print article in pdf

The Šumava/Bohemian Forest Mts./Bohemian Forest Mts. Protected Landscape Area Celebrates 60 Years

It seems almost unbelievable how long nature conservation has been in effect – and on such a large territory and at the same time so successfully. After all, a national park has been established on most of the territory of the original Šumava/Bohemian Forest Mts./Bohemian Forest Mts. Protected Landscape Area (PLA), and several dozens of new small-size Specially Protected Areas have been designated in the remaining area! Together with the Bayerischer Wald/Bavarian Forest National Park, it is a huge forest ecosystem with high level of protection and conservation: across 417,000 hectares there is no logging, within more than 30,000 hectares there is no game hunting. Therefore, Nature has been building its real cathedral there.

The complicated Šumava/Bohemian Forest Mts.

My oldest memories of the PLA issue go back to 1983. The PLA was 20 years old then, and a conference on ecological aspects of the Šumava/Bohemian Forest Mts./Bohemian Mts. range was held at Hotel Gomel (today: Clarion Congress) in the city of České Budějovice. I remember that the issue of air pollution – and the need for liming forests – was much discussed there, just as the increasing nutrient load of the Lipno Water Reservoir and the need to control tourism and build a sufficient number of wastewater treatment plants. I was also intrigued by the remark of a kind of local potentate, who complained about the remoteness of the area. As an example, he mentioned his wife, who had to take a day off to get to the town of Volary or Prachatice, if she wanted to go to the hairdresser’s.

At present, the agricultural landscape of the Šumava/Bohemian Forest Mts. Protected Landscape Area consists largely of meadows and pastures with scattered trees and fallow wetlands. © Pavel Hubený

Šumava/Bohemian Forest Mts. symbol: the Snowbell (Soldanella montana) © Pavel Hubený

Another memory I have is a seminar organised by the regional centres of monument care at Churáňov on the occasion of the 25th anniversary of the PLA. It was dominated by František Urban, criticising the construction of the Northern Boubín Road across ancient spruce forests on Mt. Boubín/Kubany, and the disastrous road below Mt. Třístoličník. These were truly massive interventions in the then compact ancient mountain spruce forests. Two other roads – to Roklanská chata/Roklan Chalet and to Pytlácký roh/Poacher’s Corner in the Modravské slatě/Modrava Moor area – were being built at the time. The reason was unfortunately facilitation of the harvesting old high-quality wood – nothing else.

The picturesque landscape and beautiful nature thus met with dissatisfaction of residents and local experts. Natural values were gradually degraded and destroyed and conservationists were toothless.

Let me give a few illustrative quotes from historical editions of the Šumava/Bohemian Forest Mts./Bohemian Forest Mts. magazine:

“… because the so-called regular management is currently so destructive, … that reserves are directly endangered without a sufficient buffer zone.” Vlastimil Heřmanský, 1985.

“Šumava/Bohemian Forest Mts./Bohemian Mts. forests are affected at elevations of over 1,000 m a.s.l. by air pollution from domestic sources but also by transfer from afar. They are damaged to the lowest degree.” Jan Novák, 1985.

“… postpone the shooting of black grouse and wood grouse cocks until after 16 April, when most hens are inseminated, to limit the shooting of old, socially superior cocks, which are the most valuable for breeding, and to limit public access to the leks.” Ivo Svatoš, 1984.

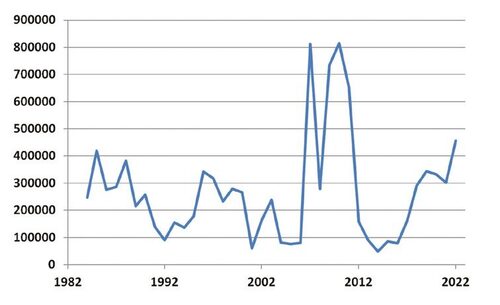

Development of salvage cutting in the present area of the Šumava/Bohemian Forest Mts. National Park from 1984 to 2022 in m³.

PLA the mother, National Park the sonny boy

For the past three decades, the Šumava/Bohemian Forest Mts. PLA has been somewhat in the shadow of Šumava/Bohemian Forest Mts. National Park. Nevertheless, it has been still persisting within the boundaries of its designation just in 1963. Today, it seems to extend over the National Park’s northern and eastern borders, but it also located below it, because the territory on which it was designated has remained formally and legislatively unchanged for 60 years. Whereas the National Park is mainly aimed at protecting spontaneous natural processes (i.e. wild nature), the PLA is different. Wild nature is also protected there, but rather in minor islands scattered over the exploited landscape. The rate of exploitation varies according to zone. Zones I and II cover roughly half of the PLA’s territory and include the most valuable ecosystems in terms of nature and the landscape. Zones III and IV focus particularly on the preservation of the historical landscape and its scenery/character which the PLA was declared in particular for.

Roots…

Already since the early 20th century, various people have sought to declare the Šumava/Bohemian Forest Mts. a national park. The most detailed proposal for a cross-border/transboundary park was made in the time of Nazi Germany in 1938. The planners of that time had delimited a large part of the Šumava/Bohemian Forest Mts. and the Bayerischer Wald/Bavarian Forest as a space for new wilderness. They even considered expelling part of the population. To a certain extent, this happened spontaneously because many inhabitants of Sudetenland feared war. The idea of establishing the Šumava/Bohemian Forest Mts. National Park returning after the end of World War II therefore had a bitter aftertaste. Despite this, Professor Julius Komárek from Charles University Prague was not afraid of publicly expressing this thought in 1946. He saw the great potential of an area where hitherto native forests grew with enclaves of wetlands and mountain meadows and grasslands/pastures. And hardly any people lived there.

What kind of landscape was it?

The sparsely populated, over large areas even completely abandoned landscape really developed in a natural way after World War II. There was not enough human power to maintain the original non-forest areas, so many of them changed into wetlands and forests rather spontaneously. Forestry was non-intensive –a report from Bavaria describes an intensive fight against the spreading European spruce bark beetle (Ips typograhus) on Bavarian side contrasting to the Czech lax approach in the neighbouring area near the village of Modrava, where no intervention against bark beetle was undertaken at all, and where its spread eventually stopped by itself. That was after the extreme drought in 1947. In largely abandoned areas of the Šumava/Bohemian Forest Mts., military settlements (Dobrá Voda and Boletice) were built along with a border zone strictly inaccessible to the public. The Šumava/Bohemian Forest Mts. became a territory on the border between two hostile political systems, and was meant to be a perfect defensive barrier. The Lipno water Reservoir did not yet exist then. Instead, the Vltava River flowed among vast peatbogs and large areas of abandoned fields and pastures, being overgrown spontaneously.

The Blanice River Canyon © Pavel Hubený

Despite a three-decade long turnover of tree generations, very old forest stands have been surviving in the Šumava/Bohemian Forest Mts. © Pavel Hubený

Association

At the time, a small group of enthusiasts, foresters, natural scientists, but simply also lovers of the Šumava/Bohemian Forest Mts.’nature again came up with the idea of establishing a large national park. At first, competent officials had made them ridiculous, but still at least a partial goal was eventually reached: instead of a national park, a protected landscape area will be established! The spiritual father of the whole action was Ladislav Vodák. In 1954, for the first time, a group of enthusiasts under his leadership formulated the idea of a national park, its extent and conservation targets. Pavel Trpák, still student at the time, was in charge of the expert/technical part of the proposal. In 1958, the Nature Conservation Corps was set up and it was the Šumava/Bohemian Forest Mts. group of the Corps who submitted their proposal to the State Institute of Monument Care and Nature Protection. The proposal was also supported by Mr. and Mrs. Leiský, who became its guarantors. The team was joined by other enthusiasts and local personalities, and in January 1960, the ‘Šumava/Bohemian Forest Mts. Group’ was commissioned to carry out a conservation survey. At that time, the proposal was already taking shape as an incentive to establish a Protected Landscape Area. The project was submitted to the Ministry of Education and Culture in September 1962, and after several reminders, the Šumava/Bohemian Forest Mts. PLA was declared on 27 December 1963.

Long waiting for conservationists

The procedure meant establishing the largest Czech PLA. Its protection was governed by Act No. 40/1956 Gazette on State Nature Conservation, and fell under the Ministry of Culture, but the different regions were responsible for its actual implementation and for rather political decision making. The District of Klatovy was the first to realise the need for a PLA Administration and established the first Administration office in the town of Sušice in 1970. It had been first led by Ladislav Vodák, but he was soon replaced by a politically more suitable figure, Karel Korec. Shortly after the Sušice office also the Vimperk office was opened. The division over two regions however meant that there were basically two Šumava/Bohemian Forest Mts. PLAs, one West Bohemian, the other South Bohemian. Therefore, the difference in approaches to nature conservation was visible everywhere, perhaps best in the zonation proposal elaborated in the second half of the 1980s. In the southern part, the most valuable Zone I had the character of isolated patches, while it included large interconnected areas in the West Bohemian zonation. It was a peculiar territory at that time. Roughly 540 km² was covered by the inaccessible border zone and the Dobrá Voda Military Training Area, another approx. 160 km² by the Boletice Military Training Area. More than 40% of the PLA’s territory was totally inaccessible to the public. It was also a completely depopulated area, almost devoid of technical infrastructure, apart from the military facilities. Restrictions resulting from the protection of the border and military areas also blocked regular farming, so most of the territory lived a natural life. In the remaining area, however, the opposite was taking place. In an effort to pursue food self-sufficiency, it was decided that built-up arable land should be compensated for by creating new areas of agricultural land in the mountains. This was called compensatory reclamation and caused the massive draining of thousands of hectares of wetlands, the elimination of hundreds of hectares of flower-rich or boggy meadows, and the destruction of many spontaneously developed forests. The introduction of large-scale agriculture led to a creation of vast drained arable fields and grasslands and to the development of large farm areas. Forests were a source of much-needed foreign currency: felled raw timber was transported to local sawmills still existing at the time, but a large part of it went straight to Western Europe without further processing. Centrally planned economy also became the cult in forestry. The consistent observance of a rotation period of around 120 years was supposed to save the communist regime. And all this was set in dramatically increasing air pollution by especially sulphur, lead and nitrogen. Spruce forests started to lose colour, and as of 1984, European spruce bark beetle started to spread. Looking back, we find that it was the 1980s when a long European spruce bark beetle outbreak started, which in four great gradations led to a gradual generational shift of the majority of Šumava/Bohemian Forest Mts.’s forests. Nonetheless, the first harbingers already appeared. In 1975, the Ministry of Culture issued a decree redefining the Šumava/Bohemian Forest Mts. PLA and establishing clearer rules and competences of the authorities in managing it. The administrations started to fulfil the role of experts formulating expert/technical standpoints for the decision-making of Regional and later District Offices – still unenforceable at the time…

Great unification and games with the border

The year 1991 not only brought the establishment of the Šumava/Bohemian Forest Mts. National Park in the bosom of the PLA, but also the unification of both Administrations into one organisation. The first zonation was made according to joint rules. The same standards for the state/public Administration performance were introduced throughout the territory. Since most political and economic interests were concentrated in the National Park, it was relatively calm in the PLA. But even so, dew ripples appeared on the water there. The land-use/territorial plan of the large territorial unit of the Šumava/Bohemian Forest Mts., approved by the Czech Government in 1992, assigned the Ministry of the Environment of the Czech Republic (ME) with the task to adjust the PLA borders to the borders of the newly delineated Šumava/Bohemian Forest Mts. Biosphere Reserve. This meant expansion of the PLA with the Kochánovské pláně/Kochanov Plains and exclusion of the Lipno Water Reservoir left bank below tzhe town of Horní Planá, so that the land-use/territorial plan would open up the area to large development projects. While the municipalities in the Kochánov area did not want to hear about a new PLA, those in the Lipno Water Reservoir area took the PLA as annulled, just waiting for the act of formalisation. I remember that time very well. The Administration prepared a list of land plots designated for exclusion from and expansion of the PLA at least three times. The ME, however, has never implemented the project. The task set by the Government later finally fell with the approval of new land-use/territorial development principles in 2007. Thus, the left bank of the Lipno Water Reservoir remained in the PLA, just as the old large-size projects for its utilisation.

The predominantly forested, picturesque landscape of the Šumava/Bohemian Forest Mts. Protected Landscape Area offers forests where you can still get lost. © Pavel Hubený

Zonation and reserves

The first PLA zonation adapted from expert/technical documents was valid from 1991 to 1994. Discussions about the new zonation in the second half of the 1990s met with opposition from farmers, foresters, and municipalities. It was the time of agricultural land privatisation and state forest redefinition. In the end, a compromise difficult for many to accept was adopted: some top ecosystems should remain in Zone II, sometimes even in Zone III. No agreement was found on a percentage: the Forests of the Czech Republic, state enterprise demanded that Zone I should cover an area not exceeding 10% (the expert proposal was 20%). The joint area of Zones I and II should not exceed half of the whole PLA. This pressure came with a gradual loss of competences. Building permit approval was no longer decided by the Administration, but by building authorities. We also lost our competence in approving tree felling outside the forest, and the Building Act gradually limited the definition of building regulations for land-use/territorial plans. The management plan, which had been discussed together with the zonation proposal, kept getting returned to the Administration by the ME for rework, so that ME finally adopted it as late as 2013. On the other hand, many sites and areas were saved from felling, privatisation or draining by designating new Specially Protected Areas. There is no point in listing the names of Specially Protected Areas declared in that time, but since 1990, a total of 73 small-size Specially Protected Areas with a total acreage of over 7,000 ha have been established (i.e. more than 4% of the original Šumava/Bohemian Forest Mts. PLA territory and 7% of the Šumava/Bohemian Forest Mts. PLA territory not covered by the Šumava/Bohemian Forest Mts. National Park). The total number of small-site Specially Protected Areas (Nature Reserves and Nature Monuments) is 81 today, and the total number of small-size Specially Protected Areas declared during the existence of the Šumava/Bohemian Forest Mts. PLA has reached a total of 92 (11 have ceased to exist).

What has changed?

Nature is dynamic and 60 years is a long time. The main drivers of change have been natural factors, mainly storms and European spruce bark beetle outbreaks, but unfortunately also privatisation and building activities. Nevertheless, forest management has gradually changed from being destructive to much more nature-friendly. Although we are confronted with deep ruts caused by timber transport and damage to natural regeneration even today, such a damage is much less frequent than we saw in the first four decades of the PLA’s existence. Forests today much more often regenerate naturally, and many more trees survive after logging, so both age and species diversity of the forests are constantly on the increase. Air pollution by sulphur and lead has vanished, and soil and water acidification has stopped. The forests are visibly recovering. Moreover, their coverage has expanded, partly by plantings, but mostly by woody plant tree self-seeding on abandoned and set-aside fallow agricultural land. Due to the forest expansion, some plant species of farmed open areas/cultural treeless habitats have even almost become extinct. The number of habitats with dwarf gentians (Gentianella spp), burnt orchids (Neotinea ustulata) and other species has decreased, but most plant species have survived and are today protected by regular habitat management. After building the Vltava River Cascade, no Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) has reached the Šumava/Bohemian Forest Mts./Bohemian Forest Mts. since 1950. On the other hand, thanks to a project by the Military Forests and Estates, state enterprise, the Eurasian lynx (Lynx lynx) was successfully re-introduced to the Šumava/Bohemian Forest Mts. in the 1980s and the Eurasian elk, in North America known as moose (Alces alces), Grey wolf (Canis lupus) and the Eurasian beaver (Castor fiber) spontaneously arrived there. Similarly, the area was repopulated by the Common raven (Corvus corax) or the Common crane (Grus grus). The PLA Administration has been successful in introducing the Ural owl (Strix uralensis), maintaining viable populations of the Freshwater pearl mussel (Margaritifera margaritifera) and the Western capercaillie (Tetrao urogallus). Despite strong decrease in numbers a Northern black grouse (Lyrurus tetrix) population has been surviving there.

Large-size nature conservation and landscape protection has thus met their targets and goals there. Despite various nature degradation and locally strong expansion of built-up areas the overwhelming part of the PLA has been under effective conservation. It would be nice if we maintain such a trend and to offer to our descendants, in addition to large wilderness areas also the landscape with all the values having been saved for sixty years: with beautiful nature, magical historic landscape scenery/character and with all native species. ■

- - - -

Cover photo:

The predominantly forested, picturesque landscape of the Šumava/Bohemian Forest Mts. Protected Landscape Area offers forests where you can still get lost. © Pavel Hubený