Nature Conservation 2023 — 5. 6. 2023 — Nature and Landscape Management — Print article in pdf

The National Commitment to Increase the Coverage and to Improve the State of Protected Areas in th

The Czech Republic, like other EU Member States, should produce a specific proposal to increase the coverage and protection, conservation and management intensity in protected areas by the end of 2022. This follows from the EU Biodiversity Strategy for 2030 (hereinafter, the 2030 Strategy), which considers effectively managed protected areas to be one of the key tools to halt the loss of biodiversity and, inter alia, expects to protect 30% of the land, of which one third strictly. The contributions of individual Member States should take into account different conditions and reflect their real importance for the biodiversity conservation. What can we realistically offer in the given time horizon? This is still a subject of professional debate. This article aims to summarize the starting points, the current state, quantify the possible liabilities and, thus, contribute to this discussion.

About the 2030 Strategy

Increasing the extent of area-based nature conservation is one of the partial components of the Green Deal, i.e. a set of strategic initiatives of the European Commission, whose basic goal is to achieve carbon neutrality in the EU by 2050. The methods for fulxxxfilling the biodiversity pillar are elaborated in the 2030 Strategy adopted by the European Commission in May 2020 (EC 2020).

Simultaneously, the key objective of the 2030 Strategy is a "Cohesive network of protected areas", to which three key commitments are to contribute by 2030:

- Legally protect a minimum of 30% of the EU’s land and 30% of the EU’s sea and integrate ecological corridors, as part of a true Trans-European Nature Network (hereinafter, the 30% target).

- Strictly protect at least a third of the EU’s protected areas, including all remaining EU primary and old-growth forests (hereinafter, the 10% target).

- Effectively manage all protected areas, define clear conservation objectives and measures, and monitor them appropriately (hereinafter, the goal of effectiveness).

Regarding the 2030 Strategy, the European Parliament adopted a resolution by which it welcomed the policy document and, inter alia, emphasized the need to fulfil all of its goals in view of the failure of the two previous strategies in this topic. It also expressed strong support for the goals in increasing the share of area-based nature conservation, including the so-called strict regime, and pointed out the necessity of their consistent implementation (EP 2021).

The Council of the EU also commented on the 2030 Strategy in its conclusions, which supported it and called for its rapid and ambitious implementation. It particularly welcomed the goals in the field of area-based protection and nature restoration and emphasized the need for collective efforts of the Member States to achieve them (COUNCIL OF THE EU 2020).

It is therefore evident that significant political support was expressed at the level of the EU institutions, formed by representatives of the Member States, for the implementation of the 2030 Strategy, often with an emphasis on the objectives in strengthening area-based nature conservation. This fact can be an important argument in promoting and defending its fulfilment.

Both the 2030 Strategy itself and its sub-objectives and their fulfilment are an important starting point for the upcoming international negotiations on the global framework for biodiversity after 2020.

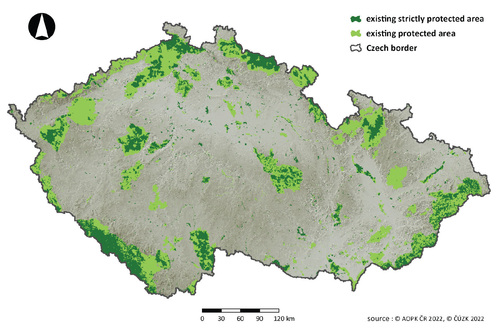

Existing protected areas in the Czech Republic with the most strictly protected parts highlighted. In dark green, all existing small-size Specially Protected Areas, Protected Landscape Areas zones I and II and all National Park zones with the exception of the cultural landscape zone – i.e. a category with the potential for strict protection. © Zdeněk Kučera & Mária Bárdyová

Criteria for selecting protected areas

In order for Member States to proceed uniformly when defining their obligations, the European Commission published guidelines in January 2022 (EC 2022), which summarize the criteria and methodology for the selection of protected areas, which should contribute to the fulfilment of the above-mentioned goals. Subsequently, in June 2022, a detailed format was published for the uniform for providing the information by individual Member States, both about sites that have already met the criteria (and can therefore be included in the initial state) and about areas through which it is proposed to achieve the 30% and 10% targets.

The content of the guidelines is the result of relatively long negotiations and four rounds of written consultations with representatives of Member States within the Nature Directives Expert Group (NADEG). The discussion within NADEG focused mainly on the realism of the goals and the considerations that led the European Commission to set them, the timetable for their implementation, financing, the necessary human capacity or the transparency of the process and, last but not least, on the so-called strict protection (see below).

From the point of view of the definitions important for the 30% target, it is worth noting that this target does not have to be fulfilled only by protected areas in the usual sense of the word, but also by means of the so-called other effective area-based conservation measures (OECM). For more information on what this relatively new concept means, see Box 1. In the Czech Republic, no territories have yet been designated as OECM. When looking at the Protected Planet database (UNEP-WCMC & IUCN 2022), it is clear that the whole of Europe is still struggling to identify OECM.

However, not every potentially identified OECM will meet the criteria that the European Commission further states in the guidelines as conditions for counting towards the 30% target. These criteria are essentially the same for both protected areas and OECM and mainly include the following principles:

- The territory is covered by some legal form of protection (legislative, administrative, or contractual);

- Its natural values and conservation objectives are defined in the territory;

- The territory has an administrator (i.e. the institution that manages it);

- The territory is managed efficiently, with established management measures ideally embodied in planning documentation;

- Monitoring of biodiversity is carried out in it.

These criteria must already be met, or the commitment of the Member State must consist in the promise of their fulfilment by 2030.

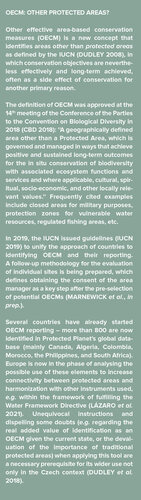

Default status – protected areas

According to current data, 1,725,672 ha (21.88%) of the Czech Republic are protected by protected areas – in the sense of Specially Protected Areas, contractually protected areas, and the EU´s Natura 2000 network sites – after deducting mutual overlaps (see Tab. 1). For the Continental Biogeographic Region the current coverage is 22.15%; in the Pannonian Biogeographical Region it is 16.02%.

We consider it undisputed that all the above categories already meet the criteria for counting towards the 30% target. Only some Natural Monuments designated primarily only for the protection of abiotic nature could be a theoretical question. However, since in the vast majority of cases typical fauna and flora inhabit the protected formation (e.g. caves, rock outcrops), which is taken into account in management plans and measures taken within the area, it would be unjustified to ignore the importance of these areas from the point of view of the 2030 Strategy's goals, even though they are usually very small in size. A separate question remains as to whether there is room for improvement in the state of all protected areas in the Czech Republic – see below.

Possible commitments to the 30% target

In order to achieve the 30% target, we therefore need a little over 8% of the Czech Republic´s territory, about 631,000 ha. Strategic considerations should be directed both towards the designation of new or expansion of existing protected areas, and towards the identification of sites outside the existing categories that fulfil the requirements for OECM and which have already been contributing significantly to the biodiversity conservation. As the 2030 Strategy also strongly emphasizes the importance of ecological corridors and the creation of a truly coherent trans-European nature network, the aspect of improving the insufficient connectivity of existing areas should play a significant role. However, it should be borne in mind that not all ecological corridors are themselves large enough and scientifically valuable enough to meet the criteria for the OECM to count towards the 30% target (HILTY et al. 2020). When choosing sites for the promise of fulfilling the 30% target, one must also pay attention to overlaps – we are looking for areas that have not yet been included among protected areas in any of the categories listed in Table 1. Let us briefly discuss the options:

Natura 2000 – the definition of the EU´s Natura 2000 network has a firm basis in European Union´s law, and its definition is a legislative obligation; it is not a voluntary strategic commitment. This process has been practically completed in the Czech Republic. In 2023, a government regulation is expected to be issued which will take into account the last outstanding requirements of the European Commission in terms of the adequacy of the system for the protection of the target species and habitats in the Czech Republic. This amendment will address, inter alia, the clarification of the borders of existing areas, and seven SACs are proposed for new designation or more significant expansion (Strážkovice, Milešov pod Milešovkou – church, Lichkov, Paseky, Nové Pole, Kozlov – Tábor, and the Východní Krušnohoří/Eastern Ore Mountains). In the advanced stage of preparations, there is also a proposal to designate a Special Protection Area in the Západní Krušné hory/Western Ore Mountains, which should primarily serve to protect one of the last populations of the Black grouse (Lyrurus tetrix) in the Czech Republic. After deduction of overlaps, these planned changes will cover 0.05% of the Czech Republic´s territory.

Large-size Specially Protected Areas – considering the designation of new Protected Landscape Areas and National Parks is certainly more than appropriate in this context. The identification of suitable sites from an expert point of view has taken place many times in the past (PEŠOUT 2015). The process of designating large-size protected areas is usually long-term, requiring close cooperation with local governments and a wide range of stakeholders. In terms of progress, the preparation of documents for the start of the discussion of the Křivoklátsko National Park, Soutok Moravy a Dyje/Morava and Dyje/Thaya Rivers Confluence Protected Landscape Area, and the Krušné hory/Ore Mountains Protected Landscape Area are now the furthest along. After deducting overlaps with existing protected areas (which are considerable in the case of Křivoklátsko and Soutok in particular), the designation of the above-mentioned areas could increase the protection in the Czech Republic´s territory by 0.8% (PEŠOUT & DORT 2022).

Small-size Specially Protected Areas – the small-size Specially Protected Areas network in the Czech Republic is extensive in terms of number, but the problem is often the very small size of individual areas (in the Czech Republic there an incredible 2,649 small-size Specially Protected Areas with an average size of 43.8 ha, but half of them is smaller than 9 ha). In this context, the emphasis on network connectivity is particularly important. Designating new small-size Specially Protected Areas together with the expansion of existing ones will continue to be an important nature conservation tool to protect the most valuable sites. Among the sites of national importance, whose proposals have already been announced, e.g. Lanžhotské pralesy/Lanžhot Primary Forests National Nature Reserve, Soutok/Confluence National Nature Monument, Obírka – Peklo NNR, and Zlatý potok/Gold Brook NNM should be mentioned. For a number of others, documents are being prepared or negotiations are being conducted at various levels, e.g. the considered national category for part of the Czechoslovak Army mine, Tok Hill NNM, Jordán Fishpond NNM, Bečva River NNR, and others. After deducting the overlaps, the number of sites of national importance currently planned for designation is at about 0.02% of the country's territory; this does not include plans to designate Nature Monuments and Nature Reserves by regional authorities in hitherto unprotected landscapes.

Contractual protection – this relatively new instrument of nature conservation (Article 39 of Act No. 114/92 Gazette on Nature Conservation and Landscape Protection, as amended later, hereinafter ANCLP) has been still used almost exclusively for the protection of Natura 2000 sites; however, there is essentially nothing preventing its wider use even in the non-protected landscape – except for the absence of practical experience with its use.

Significant Landscape Elements (SLEs) – perhaps a somewhat neglected, but legislatively relatively powerful tool for area-based protection. By their very nature, registered SLEs are sites that often meet the OECM definition, which also meet the criteria for inclusion in the 30% target – they have a designation document that defines natural values and protection objectives, the law designates an authority responsible for their management, which also provides management according to its financial possibilities. Targeted biodiversity monitoring does not take place in most of them; however, regular habitat mapping can provide valuable data on the development of ecosystems there over time. In addition to the absence of dedicated planning documentation, a significant problem is that there has currently been no central registration of VKP (ŠTEFANOVÁ 2015), so we can only estimate (based on extra-polation of data from two regions where the Nature Conservation Agency of the Czech Republic (NCA CR) data were systematically collected, checked and digitized) that registered SLEs in the Czech Republic occupy approx. 10,000 ha (about 0.13% of the country´s territory). The legal obligation to store designation documentation together with spatial data in a central database could be part of the changes in area-based protection in connection with the adoption of obligations according to the 2030 Strategy. In such a case, it would also be necessary to deal with the issue of systematic management planning in these areas.

In this context, it is also possible to consider the so called SLEs protected by law, which often protects valuable areas (fishponds, lakes, watercourses, peatlands, valley floodplains, and forests) from the biodiversity point of view and ensuring the connectivity of the landscape. However, they are not precisely spatially defined and targeted management in the sense of the criteria for the 30% target is not so clearly defined by the designation regulation. An effective solution would be to set up a record of the most valuable SLE segments, which are the bearer of the main values of the given SLEs protected by law, to give then them priority attention in terms of finances for management and monitoring. SLEs protected by law, without overlap with existing protected areas, represent about another 23% of the country's area1, however, this is the maximum proportion and realistically it would make sense to include only registered SLEs and registered segments of the SLEs protected by law according to the differentiated approach proposed above.

---

1 when counting all forest, wetland and water ecosystems from the Consolidated Layer of Ecosystems

---

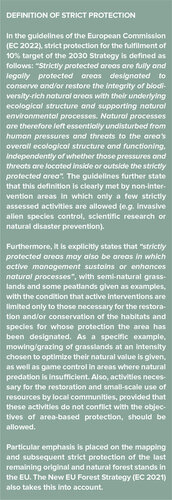

On the left, the natural zone of the Šumava/Bohemian Forest Mts. National Park, on the right, the natural zone (Naturzone) of the German Bayerischer Wald/Bavarian Forest National Park. On both sides of the state border, the areas are intended to be left undisturbed by natural processes in the future. However, they clearly differ in the time of the last intervention. © Eva Knižátková

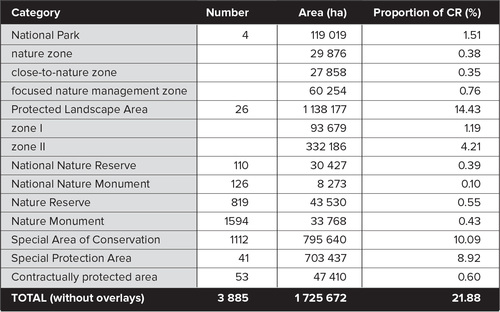

Mowing meadows in the Lopeník area in the zone II of the Bílé Karpaty/White Carpathians Mts. Protected Landscape Area. In accordance with the methodological instructions of the European Commission, it is possible to include areas where the necessary active management supports biological diversity into the so-called strict protection as well, including grazing and mowing meadows at an intensity and frequency corresponding to the ecological demands of the subject of protection. © Ivana Jongepierová

Territorial System of Ecological Stability (TSES) – even these elements (especially biocentres/core areas, probably of all levels) have the potential to be included in OECM, aimed to a certain extent at ensuring the protected area system connectivity; see also PEŠOUT & HOŠEK 2012. They partially overlap with VKP protected by law (especially forests) but there is also a problem with the absence of central records on the current TSES for the purposes of reporting or planning targeted management.

Another element of area-based protection, which significantly contributes to the biodiversity conservation and which is worth paying attention to, are private protected areas. The term is not enshrined in Czech legislation and the 2030 Strategy does not explicitly include it either; however, these areas can probably be included among the OECMs that meet the criteria for the 30% target. They include, e.g. Bird Parks established by the Czech Society for Ornithology, or sites purchased and managed by land trusts/land associations (PEŠOUT 2015). If the administrators agree, these areas could be included in the system.

Some other elements of area-based protection can also be considered among the potential OECMs, e.g. temporarily protected areas, nature parks, or military districts, protection zones for vulnerable water resources, and protective forests, although some of the established criteria are not always met. However, a detailed analysis of the OECM issue is beyond the scope of this article.

Strict 10% protection

As the sites that also protect biodiversity secondarily contribute to the 30% target, it is important to emphasize the importance and increase the coverage of those that were directly established for the purpose of biodiversity conservation and where all activities are strictly regulated so that this target is achieved. The 2030 Strategy thus quite rightly places emphasis on increasing the share of EU territory that is strictly protected.

Although it might seem that strict protection is emphasized in the 2030 Strategy exclusively in the sense of protecting natural processes and minimizing human influences, in the European Commission's instructions, targeted interventions to support biodiversity are ultimately taken into account (see Box 2 for more details). It is the result of discussions with Member States within the NADEG, where the definition of strict protection and, in its context, the role of management of areas and permissible anthropogenic activities (hunting rights, forest management, etc.) finally crystallized as a fundamental topic. As a result, the definition is looser compared to the original proposal and allows for a certain range of interventions, which must be compatible with the objectives of the protection of the given area, or they are necessary for its restoration. This topic was also discussed in this journal in 2022 (HOFMEISTER 2022, HOŠEK & STORCH 2022).

How many strictly protected areas do we already have?

If we look at the legal protection conditions and objectives of individual Specially Protected Area categories, then in general we can say that in particular the natural zones, the close-to- nature zones and the focused nature management zones in National Parks, the zones I a II of Protected Landscape Areas, (National) Nature Reserves, and to a large extent also (National) Natural Monuments have sufficiently strong (albeit differently worded) instruments for all threatening acti-vities to be regulated to the extent that they do not compromise the achievement of the area-based protection objectives. These sites without mutual overlaps now represent 7.78% of the Czech Republic (see Map); for data on the proportion of individual categories in the Czech Republic, see Table 1.

Table 1: Protected areas in the Czech Republic – current status

Note: data taken from the Central List of Nature Conservation (Ústřední seznam ochrany přírody) and valid as of 1/10/2022

It is obvious that not all specific areas falling into these categories fulfil the minimization of interventions to only those that are needed to manage or restore habitats and species. Areas and their parts mainly differ in terms of the quality of preserved natural values, and optimal management or acceptable level of use depends on the ecological requirements of individual subjects of protection and the conditions of the site. All these facts are taken into account in regularly updated management plans or principles. In reality, land ownership probably remains the most important factor for the success of implementing optimal management. The actual proportion of strictly protected areas in the sense of the ranking of the claims of subjects of protection to other uses is therefore difficult to quantify more precisely at the national level; it is probably around 3%.

Is it possible to get closer to 10%?

It is certainly possible to gradually increase the proportion of strictly protected areas from those categories that have the prerequisites for it. It is also worth considering whether the conditions of protection of the small-size Specially Protected Areas, or Protected Landscape Areas in the ANCLP would not deserve evaluation from the point of view of their adequacy, i.e. whether they are able to respond effectively enough to new pressures and threats acting in the today's landscape.

Designation of new protected areas has already been discussed above; the gradual re-designation of existing areas also plays a role in this context, including e.g. the revision of PLA zoning. In the Czech Republic, increasing the proportion of strict protection understood in this way is also in line with efforts to ensure the protection of Special Areas of Conservation (SACs under the EU Habitats Directive) in the form of the Specially Protected Area selected categories, which still have not been designated to the necessary extent. In the following period, it will be appropriate to focus on the evaluation of the effectiveness of the so-called basic protection (Article 45, letter c, Para 2, ANCLP) to maintain or improve the condition of specific SACs and, in the event of its insufficiency, to proceed with the designation of other Nature Monuments or Nature Reserves.

However, the fact that the definition of strict protection is broader does not mean that increased emphasis should not be placed on the protection of sites where we primarily protect natural processes and leave them to spontaneous development. Size is essential for this approach; small-size Specially Protected Areas and zones of large-size Specially Protected Areas that have this objective should always be defined in such a way that they are large enough for the processes to actually be applied at sufficient scales. A summary evaluation of the existing system of protected areas in terms of suitability and expediency of leaving selected ecosystems primarily exposed to natural forces (including areas affected by the extraction of mineral resources) has not yet been carried out.

Achieving the application of strict protection on 10% of the Czech Republic´s territory is an ambitious goal, which in any case will be difficult to achieve in the conditions of the Czech landscape with a tradition of use (PEŠOUT 2020), but we should at least try to get as close to it as possible.

Are our protected areas effective?

It is not sufficient just to have protected areas; protected areas need to be in good condition. They must succeed in effectively achieving the goals for which they were designated, which is very closely related, inter alia, to the above-discussed real application of strict protection. Many articles have dealt with the evaluation of the protected area effectiveness in general; for an overview at the global level, we refer to a text in one of the previous issues (PLESNÍK & PELC 2022 – see pages 77 - 81 in this issue).

And what do we actually know about the effectiveness of protected areas in the Czech Republic? So far, surprisingly little at the national level. At the level of individual sites, information can be found in the relevant assessment chapters of management plans and summaries of recommended measures. We have a very good level of planning documentation, regularly updated for most sites. It defines everything necessary – subjects of protection, goals, measures to be taken to achieve them, and often also indicators for evaluating the achievement of the favourable status.

However, what is noticeably missing is the targeting of monitoring on the effectiveness of the implemented measures. It is important to realize that, according to the 2030 Strategy, in terms of achieving the protection goals of individual protected areas, biodiversity monitoring should take place on 30% of the area. This requires significant financial and human resources. The basis should continue to be extensive and regular habitat mapping, which, however, must be supplemented with a series of the targeted monitoring as needed. Only monitoring can provide managers with information for adapting management and making decisions about the use of the site within the adaptive management cycle.

Conclusion

The 2030 Strategy provides us with a mandate, a guide, and a starting point for expanding one of the most effective tools for nature conservation. Area-based protection is a very important part of efforts to preserve biodiversity, which allows us to plan the management of certain relatively geographically integral natural units, has its pan-European tradition and, to a large extent, the support of the public. However, it is becoming more and more clear that we cannot solve the problem of declining biodiversity in protected areas, and we must also focus our efforts on the landscape outside them and towards its restoration, so that it is more resistant to climate change impacts, and is therefore able to adequately respond to the needs of society (in terms of food production, economy, local communities, etc.), even though the role of protected areas is traditional and irreplaceable in this as well. Both of these efforts should therefore complement each other appropriately, for which at least European Union initiatives and the legislative environment provide us with a good basis.

---

Acknowledgments – The authors thank Zdeněk Kučera and Mária Bárdyová for performing the analyses and elaborating the map, and Pavel Pešout for checking the text and providing valuable comments.