Nature Conservation 2021 — 10. 6. 2021 — On Nature in the Czech Republic — Print article in pdf

European Transboundary Protected Areas: Bohemian-Saxon Switzerland

With this article we start a series on transboundary protected areas certified under the Transboundary Parks programme of the EUROPARC Federation. The programme was a follow-up of initiatives taken earlier in the IUCN, inter alia, at the launch of the Parks for Life programme (1994, Priority project 22), and started soon after the fall of the Iron Curtain in Central and Eastern Europe, opening up previously unimaginable possibilities. Jan Čeřovský was a Czech representative strongly engaged in these activities.

In 1996, the IUCN published the proceedings of an international conference entitled as Biodiversity Conservation in Transboundary Protected Areas in Europe (Čeřovský 1996), which took place in the town of Chřibská. Thanks to this conference, the attention of nature conservationists from many countries was drawn to the transboundary region of Saxon-Bohemian Switzerland – a National Park already on the Saxon side, but in a (very demanding) preparatory stage on the Czech side. Lively experience with this Bohemian-Saxon collaboration and conclusions derived from it (Hentschel & Stein 1996) captured in this publication has been still relevant today (see Box).

In 1999, in collaboration with the EUROPARC Federation, IUCN also published an essential comprehensive publication entitled as Transboundary Protected Areas in Europe (Brunner 1999), which basically determined the direction of transboundary collaboration in Europe, its potential, but also its obvious restrictions, to a large extent. The ideas outlined there eventually led to the establishment of a relatively robust system of evaluation, verification and certification of transboundary collaboration, based on detailed criteria (Basic Standards). Transboundary Parks is one of the most successful EUROPARC Federation´s programmes, moreover unique on a global scale. It was therefore presented at the IUCN World Park Congress in Sydney (2014) on the example of the Krkonoše/Giat Mts. and Saxon-Bohemian Switzerland (Hošek et al. 2015).

Since Europe consists of many, predominantly small countries, transboundary collaboration is not only a welcome benefit, but in many cases a necessary condition for a range of protected areas to function well. In some cases, the existence of a partner protected area on the other side of the border has played an essential role in protected area designation or strengthening the conservation level. Examples are the re-designation of (part of) a Protected Landscape Area (PLA) into a national park. The Sächsische Schweiz National Park (1990) played an essential role in the designation of the Bohemian Switzerland National Park (2000).

Similarly, the Podyjí/Thaya River Basin National Park (1991) in the Czech Republic inspired the designation of the Thayatal National Park (2000) in Austria.

In many cases, transboundary protected areas have had a long tradition, dating back to a time long before the official pan-European activities. We consider the first one to be the Pieniny Mts. (1932, Czechoslovakia/Poland). In a range of other cases, transboundary protected areas unfortunately exist only on maps, where they border each other, but real collaboration is absent or very rare. Areas certified by the EUROPARC Federation thus represent a mere fraction of the total number of transboundary protected areas. They meet relatively strict certification criteria, while EUROPARC Federation membership and of course interest and determination to undergo the evaluation process are conditions as well. It should be mentioned that although the certification criteria are equal for all candidates, the conditions of the particular protected areas to be met can differ diametrically. Just imagine on the one hand the bilateral Krkonoše/Karkonosze National Park with a very low language barrier, a long tradition of collaboration and a practically absent border within the Schengen area, and on the other hand the extensive (1,889 km2) trilateral protected area (different categories) Pasvik-Inari on the territories of Norway, Finland and Russia with an almost impermeable border between the EU and Russia and a strong language barrier. Not without reason, transboundary collaboration runs there under the motto ‘Borders separate – Nature unites!’ However, from regular meetings of the European certified protected area,family called TransParcNet, it follows unequivocally that despite all pitfalls, the collaboration is essential, not only for nature and its protection, conservation and management but also for the people living and working in these areas. It is exactly such a type of diversity that enriches much more than it burdens. The present series of articles aims at providing examples of good practice from these areas.

Bohemian Switzerland National Park 20 years, Saxon Switzerland National Park 30 years

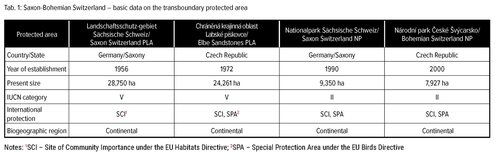

It is unnecessary to introduce Saxon-Bohemian Switzerland to the readers (in contrast to 20 years ago). Basic data on the transboundary protected area are given in the Box.

It clearly shows that a transboundary protected area certified under the Transboundary Parks programme consists there of not only two National Parks, but also two Protected Landscape Areas.

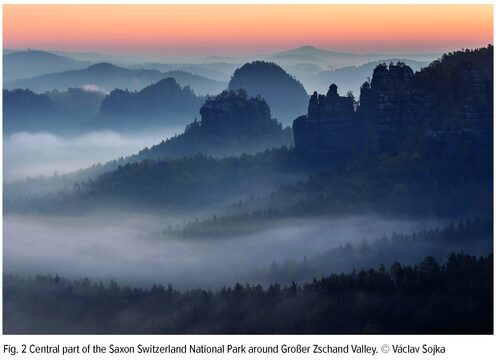

The following facts should be mentioned to briefly characterise Saxon-Bohemian Switzerland in superlatives and strong terms.

- It is the largest sandstone-rock area in Europe.

- It has the widest elevation range (over 600 m, between Mt. Vysoký Sněžník and the Elbe River, the lowest location in the whole Czech Republic) of all sandstone areas in the Bohemian Cretaceous Basin.

- Logically, a range of species reaches its lowest elevation in the Czech Republic there; they include mountainous and Artic-alpine species associated with climate inversion in deep ravines and gorges.

- Not only the extensive compact sandstone area of both National Parks, but also the Elbe River sandstone canyon and the table mountain landscape with Mt. Děčínský Sněžník in the west and a range of table mountains on the Saxon side are unique in Europe.

- We can find the largest sandstone arch in Europe (Pravčice/Prebischtor Gate National Nature Monument).

- Areas accessible to tourists have had a long history. The Gebirgsverein für die Böhmische Schweiz, established in 1878, is the oldest organisation of its type in the present Czech Republic.

Recently a number of scientific publications on Saxon-Bohemian Switzerland have been published. Monographies include Sandstone Landscapes, evaluating the position of the above area in the broader context of sandstone areas in Europe (Härtel et al. 2007), further the book Pravčická brána / Das Prebischtor (Vařilová et Belisová 2010), and especially the latest publication Geologie Českosaského Švýcarska (Geology of Saxon-Bohemian Switzerland – Vařilová 2020).

In 2020, both National Parks celebrate a jubilee: Bohemian Switzerland 20 years of existence, Saxon Switzerland 30 years. On the occasion of the previous jubilees (15th and 25th anniversary, respectively), a review was published in Ochrana přírody/Nature Conservation Journal (Härtel et al. 2015). Summarising the principal changes which the Bohemian Switzerland National Park area and its Administration have undergone in the past five years, particularly the following facts should be mentioned.

(1) As the result of an amendment of the Nature Conservation and Landscape Protection Act, the NP Administration has become an organisation partly funded from the State Budget (unification of the economic model with other Czech National Parks) and now also performs public administration in nature conservation for the Labské pískovce/Elbe Sandstones PLA (unification of the model with the Šumava/Bohemian Forest Mts. NP and PLA). This change ensures that the PLA will be able to fully perform its function as a ‘buffer zone’, which is not legislated as such with regards to the existence of a PLA.

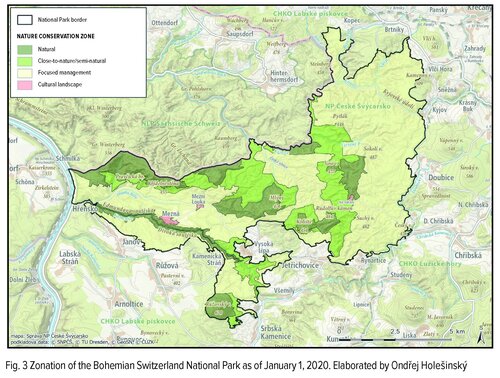

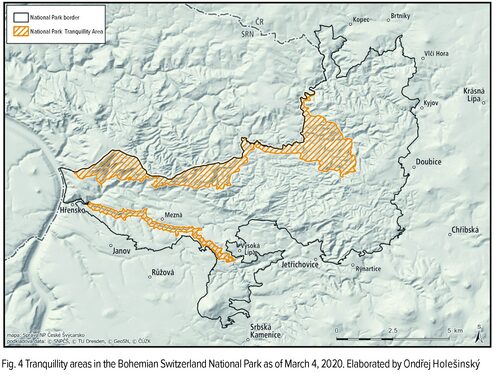

(2) The NP territory has a new zonation (see Fig. 3) and has delineated Tranquillity Areas (Fig. 4).

(3) In 2018 the Saxon-Bohemian Switzerland Transboundary Scientific Council was established as an advisory, consultative and subsidiary body of the two National Park Administrations in research and documentation on both sides of the border. Its activity covers the whole area of both National Parks and the Elbe Sandstones and Saxon Switzerland Protected Landscape Areas. The council includes experts from various fields, and academics from the Bohemian and Saxon sides.

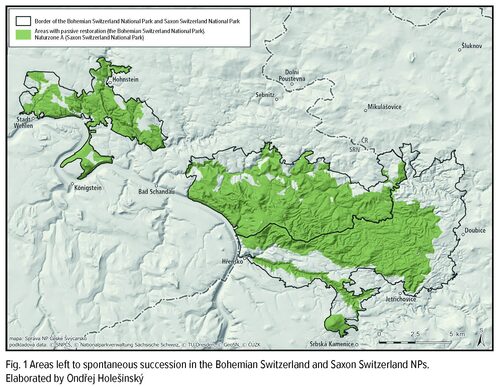

(4) The practically most important change is however the dramatic transformation of the National Park which has currently been taking place as a result of the European spruce bark beetle (Ips typographus) outbreak For the NP´s area, it means, inter alia, a rapid growth in areas left to spontaneous succession, linked to an adjacent territory on the Saxon side with a similar regime (Naturzone), leading to a central transboundary area at a total size of approx. 10,000 ha (Fig. 1) where natural forest dynamics will prevail. However, systematic eradication of selected invasive species (especially Pinus strobus), one of the main and long-term management objectives since the establishment of the NP, will continue.

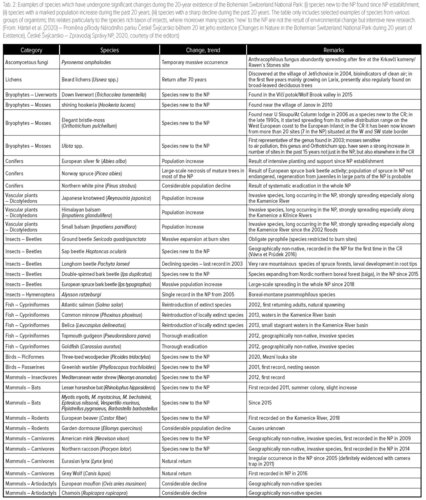

(5) Besides fundamental ecosystem changes, also many changes at the species level can be found, although these are far from being so dramatic. Examples of the species which have undergone significant changes during the entire 20-year existence of the Bohemian Switzerland National Park are given in Tab. 2.